Source edited from: Wikipedia History of the Alphabet

Most or nearly all alphabetic scripts used throughout the world today ultimately go back to the proto-alphabet consonantal writing system used for Semitic languages in the Levant in the 2nd millennium BCE. Mainly through Phoenician and Aramaic, two closely related members of the Semitic family of scripts used during the early first millennium BCE, the Semitic alphabet became the ancestor of multiple writing systems across the Middle East, Europe, northern Africa and South Asia.

Some modern authors distinguish between:

- consonantal scripts of the Semitic type, called “abjads“, where each symbol usually stands for a consonant.

- “true alphabets” consistently assign letters to both consonants and vowels on an equal basis.

In this sense, the first true alphabet was the Greek alphabet, which was adapted from the Phoenician. Latin, the most widely used alphabet today, in turn derives from Greek (by way of Cumae and the Etruscans).

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Hieroglyphs were employed in three ways in Ancient Egyptian texts: as logograms (ideograms) that represent a word denoting an object pictorially depicted by the hieroglyph; more commonly as phonograms writing a sound or sequence of sounds; and as determinatives (which provide clues to meaning without directly writing sounds). Since vowels were mostly unwritten, the hieroglyphs which indicated a single consonant could have been used as a consonantal alphabet (or “abjad”). This was not done when writing the Egyptian language, but seems to have been significant influence on the creation of the first alphabet (used to write a Semitic language).

Mesopotamian cuneiform

Proto-Sinaitic

Developed in Ancient Egypt to represent the language of Semitic-speaking workers in Egypt. This script was partly influenced by the older Egyptian hieratic, a cursive script related to Egyptian hieroglyphs. It has yet to be fully deciphered. However, it may be alphabetic and probably records the Canaanite language. The oldest examples are found as graffiti in the Wadi el Hol and date to perhaps 1850 BCE. The table below shows hypothetical prototypes of the Phoenician alphabet in Egyptian hieroglyphs. Several correspondences have been proposed with Proto-Sinaitic letters.

| Possible Egyptian prototype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenician | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Possible acrophony | ʾalp ox | bet house | gaml throwstick/camel | digg fish/door | haw, hillul jubilation | waw hook | zen, ziqq handcuff | ḥet courtyard/fence | ṭēt wheel | yad arm | kap hand |

| Possible Egyptian prototype |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenician | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Possible acrophony | lamd goad | mem water | nun large fish/snake | samek fish | ʿen eye | piʾt bend | ṣad plant | qup monkey/cord of wool | raʾs head | šananuma bow | taw signature |

This Semitic script adapted Egyptian hieroglyphs to write consonantal values based on the first sound of the Semitic name for the object depicted by the hieroglyph (the “acrophonic principle”). So, for example, the hieroglyph per (“house” in Egyptian) was used to write the sound [b] in Semitic, because [b] was the first sound in the Semitic word for “house”, bayt. The script was used only sporadically, and retained its pictographic nature, for half a millennium, until adopted for governmental use in Canaan.

Phoenician

The first Canaanite states to make extensive use of the alphabet were the Phoenician city-states and so later stages of the Canaanite script are called Phoenician. The Phoenician cities were maritime states at the center of a vast trade network and soon the Phoenician alphabet spread throughout the Mediterranean. Two variants of the Phoenician alphabet had major impacts on the history of writing: the Aramaic alphabet and the Greek alphabet.

Aramaic

The Aramaic alphabet, which evolved from the Phoenician in the 7th century BCE as the official script of the Persian Empire, appears to be the ancestor of nearly all the modern alphabets of Asia:

- The modern Hebrew alphabet started out as a local variant of Imperial Aramaic. (The original Hebrew alphabet has been retained by the Samaritans.)

- The Arabic alphabet descended from Aramaic via the Nabataean alphabet of what is now southern Jordan.

- The Syriac alphabet used after the 3rd century CE evolved, through Pahlavi and Sogdian, into the alphabets of northern Asia, such as Orkhon (probably), Uyghur, Mongolian, and Manchu.

- The Georgian alphabet is of uncertain provenance, but appears to be part of the Persian-Aramaic (or perhaps the Greek) family.

Greek alphabet

By at least the 8th century BCE the Greeks borrowed the Phoenician alphabet and adapted it to their own language, creating in the process the first “true” alphabet, in which vowels were accorded equal status with consonants.

The letters of the Greek alphabet are the same as those of the Phoenician alphabet, and both alphabets are arranged in the same order.

However, whereas separate letters for vowels would have actually hindered the legibility of Egyptian, Phoenician, or Hebrew, their absence was problematic for Greek, where vowels played a much more important role. The Greeks used for vowels some of the Phoenician letters representing consonants which weren’t used in Greek speech. All of the names of the letters of the Phoenician alphabet started with consonants, and these consonants were what the letters represented, something called the acrophonic principle However, several Phoenician consonants were absent in Greek, and thus several letter names came to be pronounced with initial vowels. Since the start of the name of a letter was expected to be the sound of the letter (the acrophonic principle), in Greek these letters came to be used for vowels. For example, the Greeks had no glottal stop or voiced phuaryngeal sounds, so the Phoenician letters ’alep and `ayin became Greek alpha and ‘ o ‘ (later renamed o micron , and stood for the vowels /a/ and /o/ rather than the consonants /ʔ/ and /ʕ/. As this fortunate development only provided for five or six (depending on dialect) of the twelve Greek vowels, the Greeks eventually created digraphs and other modifications, such as ei,

ou, and o which became omega), or in some cases simply ignored the deficiency, as in long a, i, u.

Several varieties of the Greek alphabet developed. One, known as Western Greek or Chalcidian, was used west of Athens and in southern Italy. The other variation, known as Eastern Greek, was used in Asia Minor (also called Asian Greece i.e. present-day aegean Turkey). The Athenians (c. 400 BCE) adopted that latter variation and eventually the rest of the Greek-speaking world followed. After first writing right to left, the Greeks eventually chose to write from left to right, unlike the Phoenicians who wrote from right to left. Many Greek letters are similar to Phoenician, except the letter direction is reversed or changed, which can be the result of historical changes from right-to-left writing to boustrophedon to left-to-right writing.

Greek is in turn the source for all the modern scripts of Europe. The alphabet of the early western Greek dialects, where the letter eta remained an h, gave rise to the Old Italic and from these Old Roman alphabet derived. In the eastern Greek dialects, which did not have an /h/, eta stood for a vowel, and remains a vowel in modern Greek and all other alphabets derived from the eastern variants: Glagolitic, Cyrillic, Armenian, Gothic (which used both Greek and Roman letters), and perhaps Georgian.

Latin alphabet

A tribe known as the Latins, who became known as the Romans, also lived in the Italian peninsula like the Western Greeks. From the Etruscans, a tribe living in the first millennium BCE in central Italy, and the Western Greeks, the Latins adopted writing in about the seventh century. In adopted writing from these two groups, the Latins dropped four characters from the Western Greek alphabet. They also adapted the Etruscan letter F, pronounced ‘w,’ giving it the ‘f’ sound, and the Etruscan S, which had three zigzag lines, was curved to make the modern S. To represent the G sound in Greek and the K sound in Etruscan, the Gamma was used. These changes produced the modern alphabet without the letters G, J, U, W, Y, and Z, as well as some other differences.

C, K, and Q in the Roman alphabet could all be used to write both the /k/ and /ɡ/ sounds; the Romans soon modified the letter C to make G, inserted it in seventh place, where Z had been, to maintain the gematria (the numerical sequence of the alphabet). Over the few centuries after Alexander the Great conquered the Eastern Mediterranean and other areas in the third century BCE, the Romans began to borrow Greek words, so they had to adapt their alphabet again in order to write these words. From the Eastern Greek alphabet, they borrowed Y and Z, which were added to the end of the alphabet because the only time they were used was to write Greek words.

The Anglo-Saxons began using Roman letters to write Old English as they converted to Christianity, following Augustine of Canterbury’s mission to Britain in the sixth century. Because the Runic wen, which was first used to represent the sound ‘w’ and looked like a p that is narrow and triangular, was easy to confuse with an actual p, the ‘w’ sound began to be written using a double u. Because the u at the time looked like a v, the double u looked like two v’s, W was placed in the alphabet by V. U developed when people began to use the rounded U when they meant the vowel u and the pointed V when the meant the consonant V. J began as a variation of I, in which a long tail was added to the final I when there were several in a row. People began to use the J for the consonant and the I for the vowel by the fifteenth century, and it was fully accepted in the mid-seventeenth century.

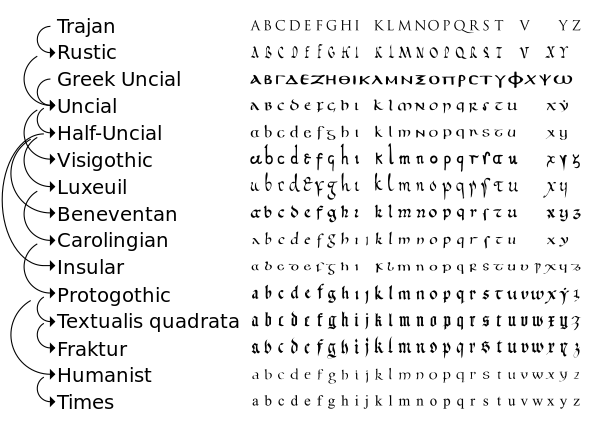

Table above shows simplified relationship between various scripts leading to the development of modern lower case of standard Latin alphabet and that of the modern variants:

- Fraktur (used in Germany until recently)

- Insular/Gaelic (Ireland).

- half-uncial and uncial, which derive from Roman cursive and Greek uncial, and Visigothic, Merovingian (Luxeuil variant here) and Beneventan.

- Carolingian script was the basis for blackletter and humanist.

- It should be noted that what is commonly called “gothic writing” is technically called blackletter (here Textualis quadrata) and is completely unrelated to Visigothic script. The letter j is i with a flourish; u and v were the same letter in early scripts and were used depending on their position in insular half-uncial and caroline minuscule and later scripts; w is a ligature of vv; in insular the runewynn is used as a w (three other runes in use were the thorn (þ), ʻféʼ (ᚠ) as an abbreviation for cattle/goods and maðr (ᛘ) for man). The letters y and z were very rarely used; þ was written identically to y, so y was dotted to avoid confusion; the dot was adopted for i only after late-Caroline (protgothic); in Benevetan script the macron abbreviation featured a dot above. Lost variants such as r rotunda, ligatures and scribal abbreviation marks are omitted; long s (ſ) is shown when no terminal s (surviving variant) is present.

- Humanist script was the basis for Venetian types which have changed little to this day, such as Times New Roman (a serifed typeface)

Letter names and order

The order of the letters of the alphabet is attested from the fourteenth century BCE in the town of Ugarit on Syria’s northern coast.Tablets found there bear over one thousand cuneiform signs, but these signs are not Babylonian and there are only thirty distinct characters. About twelve of the tablets have the signs set out in alphabetic order. There are two orders found, one of which is nearly identical to the order used for Hebrew, Greek and Latin, and a second order very similar to that used for Ethiopian.

It is not known how many letters the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet had nor what their alphabetic order was. Among its descendants, the Ugaritic alphabet had 27 consonants, the South Arabian alphabets had 29, and the Phoenician alphabet 22. These scripts were arranged in two orders, an ABGDE order in Phoenician and an HMĦLQ order in the south; Ugaritic preserved both orders. Both sequences proved remarkably stable among the descendants of these scripts.

The letter names proved stable among the many descendants of Phoenician, including Samaritan, Aramaic, Syriac, Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek alphabet. However, they were largely abandoned in Tifinagh, Latin and Cyrillic. The letter sequence continued more or less intact into Latin, Armenian, Gothic, and Cyrillic, but was abandoned in Brahmi, Runic, and Arabic, although a traditional abjadi order remains or was re-introduced as an alternative in the latter.

The table is a schematic of the Phoenician alphabet and its descendants.

| nr. | Reconstruction | IPA | value | Ugaritic | Phoenician | Hebrew | Arabic | Greek | Latin | Cyrillic | Runic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ʾalpu “ox” | /ʔ/ | 1 | א ʾālef | ﺍ ʾalif | Α alpha | A | А azŭ | ᚨ *ansuz | ||

| 2 | baytu “house” | /b/ | 2 | ב bēṯ | ﺏ bāʾ | Β bēta | B | В vĕdĕ, Б buky | ᛒ *berkanan | ||

| 3 | gamlu “throwstick” | /ɡ/ | 3 | ג gīmel | ﺝ jīm | Γ gamma | C, G | Г glagoli | ᚲ *kaunan | ||

| 4 | daltu “door” / diggu “fish” | /d/, /ð/ | 4 | ד dāleṯ | ﺩ dāl, ذ ḏāl | Δ delta | D | Д dobro | |||

| 5 | haw “window” / hallu “jubilation“ | /h/ | 5 | ה hē | ﻫ hāʾ | Ε epsilon | E | Е ye, Є estĭ | |||

| 6 | wāwu “hook” | /β/ or /w/ | 6 | ו vāv | و wāw | Ϝ digamma, Υ upsilon | F, V, Y | Ѹ / Ꙋ ukŭ → У | ᚢ *ûruz / *ûram | ||

| 7 | zaynu “weapon” / ziqqu “manacle” | /z/ | 7 | ז zayin | ز zayn or zāy | Ζ zēta | Z | Ꙁ / З zemlya | |||

| 8 | ḥaytu “thread” / “fence”? | /ħ/, /x/ | 8 | ח ḥēṯ | ح ḥāʾ, خ ḫāʾ | Η ēta | H | И iže | ᚺ *haglaz | ||

| 9 | ṭaytu “wheel” | /tˤ/, /θˤ/ | 9 | ט ṭēṯ | ط ṭāʾ, ظ ẓāʾ | Θ thēta | Ѳ fita | ||||

| 10 | yadu “arm” | /j/ | 10 | י yōḏ | ي yāʾ | Ι iota | I | І ižei | ᛁ *isaz | ||

| 11 | kapu “hand” | /k/ | 20 | כ ך kāf | ك kāf | Κ kappa | K | К kako | |||

| 12 | lamdu “goad” | /l/ | 30 | ל lāmeḏ | ل lām | Λ lambda | L | Л lyudiye | ᛚ *laguz / *laukaz | ||

| 13 | mayim “waters” | /m/ | 40 | מ ם mēm | م mīm | Μ mu | M | М myslite | |||

| 14 | naḥšu “snake” / nunu “fish” | /n/ | 50 | נ ן nun | ن nūn | Ν nu | N | Н našĭ | |||

| 15 | samku “support” / “fish” ? | /s/ | 60 | ס sāmeḵ | Ξ ksi, (Χ ksi) | (X) | Ѯ ksi, (Х xĕrŭ) | ||||

| 16 | ʿaynu “eye” | /ʕ/, /ɣ/ | 70 | ע ʿayin | ع ʿayn, غ ġayn | Ο omikron | O | О onŭ | |||

| 17 | pu “mouth” / piʾtu “corner” | /p/ | 80 | פ ף pē | ف fāʾ | Π pi | P | П pokoi | |||

| 18 | ṣadu “plant” | /sˤ/, /ɬˤ/ | 90 | צ ץ ṣāḏi | ص ṣād, ض ḍād | Ϻ san, (Ϡ sampi) | Ц tsi, Ч črvĭ | ||||

| 19 | qupu “Copper”? | /kˤ/ or /q/ | 100 | ק qōf | ق qāf | Ϙ koppa | Q | Ҁ koppa | |||

| 20 | raʾsu “head” | /r/ or /ɾ/ | 200 | ר rēš | ر rāʾ | Ρ rho | R | Р rĭtsi | ᚱ *raidô | ||

| 21 | šinnu “tooth” / šimš “sun“ | /ʃ/, /ɬ/ | 300 | ש šin/śin | س sīn, ش šīn | Σ sigma, ϛ stigma | S | С slovo, Ш ša, Щ šta, Ꙃ / Ѕ dzĕlo | ᛊ *sowilô | ||

| 22 | tawu “mark” | /t/, /θ/ | 400 | ת tāv | ت tāʾ, ث ṯāʾ | Τ tau | T | Т tvrdo | ᛏ *tîwaz |

These 22 consonants account for the phonology of Northwest Semitic. Of the 29 consonant phonemes commonly reconstructed for Proto-Semitic, seven are missing: the interdental fricatives ḏ, ṯ, ṱ, the voiceless lateral fricatives ś, ṣ́, the voiced uvular fricative ġ, and the distinction between uvular and pharyngeal voiceless fricatives ḫ, ḥ, in Canaanite merged in ḥet. The six variant letters added in the Arabic alphabet include these (except for ś, which survives as a separate phoneme in Ge’ez ሠ): ḏ → ḏāl; ṯ → ṯāʾ; ṱ → ḍād; ġ → ġayn; ṣ́ → ẓāʾ; ḫ → ḫāʾ

Complex derivations and independent alphabets

Although this description presents the evolution of scripts in a linear fashion, this is a simplification. For example, the Manchu alphabet, descended from the abjads of West Asia, was also influenced by Korean hangul, which was either independent (the traditional view) or derived from the abugidas of South Asia. Georgian apparently derives from the Aramaic family, but was strongly influenced in its conception by Greek. A modified version of the Greek alphabet, using an additional half dozen demotic hieroglyphs, was used to write Coptic Egyptian. Then there is Cree syllabics (an abugida), which is a fusion of Devanagari and Pitman shorthand developed by the missionary James Evans.

Possible independently invented alphabets are:

- Meroitic alphabet, a 3rd-century BCE adaptation of hieroglyphs in Nubia to the south of Egypt

- Rongorongo script of Easter Island.

- Maldivian script, which is unique in that, although it is clearly modeled after Arabic and perhaps other existing alphabets, it derives its letter forms from numerals.

- Korean Hangul, which was created independently in 1443.

- Osmanya alphabet was devised for Somali in the 1920s by Osman Yusuf Kenadid, and the forms of its consonants appear to be complete innovations.

- Zhuyin phonetic alphabet derives from Chinese characters.

- Santali alphabet of eastern India appears to be based on traditional symbols such as “danger” and “meeting place”, as well as pictographs invented by its creator. (The names of the Santali letters are related to the sound they represent through the acrophonic principle, as in the original alphabet, but it is the final consonant or vowel of the name that the letter represents: le “swelling” represents e, while en “thresh grain” represents n.)

- In early medieval Ireland, Ogham consisted of tally marks

- monumental inscriptions of the Old Persian Empire were written in an essentially alphabetic cuneiform script whose letter forms seem to have been created for the occasion.