Tag: modernism

-

International Swiss Style

Overview Experimental Jetset Lars Muller Norm Wim Crouwel edited from Wikipedia International Topographic Style The International Typographic Style, also known as the Swiss Style, is a graphic design style that emerged in Russia, the Netherlands and Germany in the 1920s and developed by designers in Switzerland during the 1950s. The International Typographic Style has…

-

Good Typography

General overviews of standard ‘rules’ Chris Do from Futur Dynamic Design Shawn Barry

-

James Goggin

Practice website archive It’s Nice That James Goggin is a Chicago-based British and/or Australian art director and graphic designer from London via Sydney, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Auckland, and Arnhem. Together with partner Shan James, he runs a design practice named Practise working with clients across Europe, Asia, Australasia, and North America. James has taught at…

-

Massimo Vignelli

Google Images Vignelli Associates website Massimo Vignelli (1931 – 2014) was an Italian designer who worked firmly within the Modernist tradition. He focused on simplicity through the use of basic geometric forms in all his work. He worked in a number of areas ranging from package design through houseware design and furniture design to public…

-

Kurt Schwitters

Kurt Hermann Eduard Karl Julius Schwitters (1887 – 1948) was a German artist painter, sculptor, graphic designer, typographer and writer. He worked in several genres and media, including Dada, Constructivism, Surrealism, poetry, sound, and what came to be known as installation art. He is most famous for his collages, called Merz Pictures. Studied at the School…

-

Joseph Muller Brockman

Josef Müller-Brockmann (May 9, 1914 – August 30, 1996) was a Swiss graphic designer and teacher. He is recognised for his simple designs and his clean use of typography (notably Akzidenz-Grotesk), shapes and colours which inspire many graphic designers in the 21st century. Each letter has its own personality …the forms of letters can create simultaneously…

-

Modernist Typography

Modernist typography emerged in Russia, the Netherlands and Germany in the 1920’s as part of broader art, architecture and design movements like Constructivism and Suprematism in Russia, Bauhaus in Germany and de Stijl in Netherlands. In 1950s designers in Switzerland developed a distinctive Swiss Style. During World War II many modernist designers fled to Britain and America to…

-

Bauhaus

Typography One of the most essential components of the Bauhaus was the effective use of rational and geometric letterforms. Moholy-Nagy and Albers believed that sans serif typefaces were the future. Stencil by Joseph Albers: Albers designed a series of stencil faces while teaching at the Dessau Bauhaus. The typeface is based on a limited palette…

-

Constructivism

Constructivist typography Google images A movement with origins in Russia, Constructivism was primarily an art and architectural movement. It rejected the idea of art for arts’ sake and the traditional bourgeois class of society to which previous art had been catered. Instead it favored art as a practise directed towards social change or that would…

-

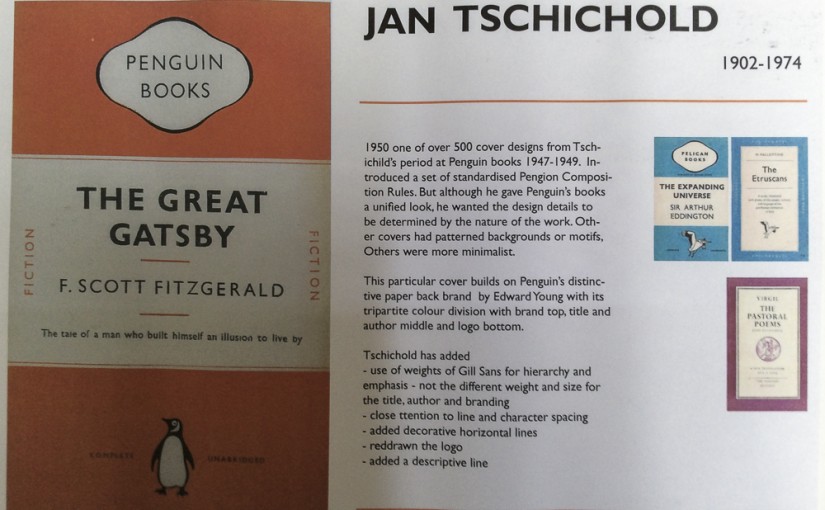

Jan Tschichold

JanTschichold (1902- 1974) was a typographer, book designer, teacher and writer. Modernism Tschichold became a convert to Modernist design principles in 1923 after visiting the first Weimar Bauhaus exhibition. He wrote an influential 1925 magazine supplement; then had a 1927 personal exhibition. Die neue Typographie Google images a manifesto of his theories of modern design and codified many other Modernist…