Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (1890 – 1941), better known as El Lissitzky was a Russian artist, designer, photographer, typographer, polemicist and architect. He was an important figure of the Russian avant garde, helping develop suprematism with his mentor, Kazimir Malevich, and designing numerous exhibition displays and propaganda works for the former Soviet Union. His work greatly influenced the Bauhaus and constructivist movements, and he experimented with production techniques and stylistic devices that would go on to dominate 20th-century graphic design.

El Lissitzky was devoted to the idea of creating art with power and purpose, art that could invoke change and saw the artist of an agent of change. “das zielbewußte Schaffen” (goal-oriented creation).

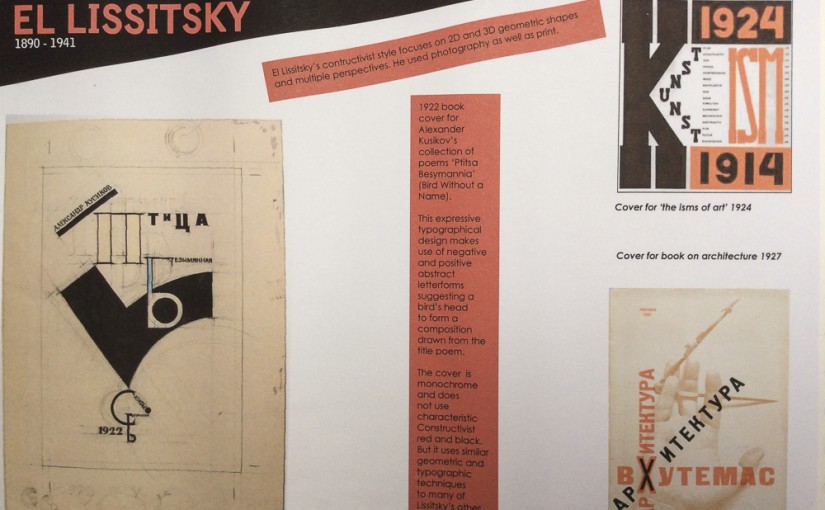

Book and Graphic Design

Lissitsky’s work with book and periodical design was perhaps some of his most accomplished and influential. He perceived books as permanent objects that were invested with power. This power was unique in that it could transmit ideas to people of different times, cultures, and interests, and do so in ways other art forms could not.

In contrast to the old monumental art [the book] itself goes to the people, and does not stand like a cathedral in one place waiting for someone to approach . . . [The book is the] monument of the future.

Lissitzky began his career illustrating Yiddish children’s books in an effort to promote Jewish culture in Russia, a country that was undergoing massive change at the time and that had just repealed its antisemitic laws. In a visual retelling of the traditional Jewish Passover song Had gadya (One Goat)which El Lissitzky integrated letters with images through a system that matched the color of the characters in the story with the word referring to them. In the designs for the final page , El Lissitzky depicts the mighty “hand of God” slaying the angel of death, who wears the tsar’s crown. Visual representations of the hand of God would recur in numerous pieces throughout his entire career, most notably with his 1925 photomontage self-portrait The Constructor, which prominently featured the hand.

In the late 1920s Lissitzky began experimenting with print media again. He launched radical innovations in typography and photomontage. He even designed a photomontage birth announcement in 1930 for his recently born son, Jen. The image itself is seen as being another personal endorsement of the Soviet Union, as it superimposed an image of the infant Jen over a factory chimney, linking Jen’s future with his country’s industrial progress.

In the late 1930s Lissitzky’s work on the USSR im Bau (USSR in construction) magazine took his experimentation and innovation with book design to an extreme. In issue #2 he included multiple fold-out pages, presented in concert with other folded pages that together produced design combinations and a narrative structure that was completely original. Each issue focused on a particular issue of the time – a new dam being built, constitutional reforms, Red Army progress and so on.

Prouns

In May 1919, on invitation from fellow Jewish artist Marc Chagall, El Lissitzky returned to Vitebsk to teach graphic arts, printing, and architecture at the newly formed People’s Art School. Chagall also invited other Russian artists, most notably the painter and art theoretician Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky’s former teacher, Yehuda Pen.

1919 propaganda poster “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge”. The image of the red wedge shattering the white form, simple as it was, communicated a powerful message that left no doubt in the viewer’s mind of its intention. The piece is often seen as alluding to the similar shapes used on military maps and, along with its political symbolism, was one of El Lissitzky’s first major steps away from Malevich’s non-objective suprematism into a style his own.

In January 17, 1920, Malevich and El Lissitzky co-founded the short-lived Molposnovis (Young followers of a new art), a proto-suprematist association of students, professors, and other artists. After a brief and stormy dispute between “old” and “young” generations, and two rounds of renaming, the group reemerged as UNOVIS (Exponents of the new art) in February. The group, disbanded in 1922, but was pivotal in the dissemination of suprematist ideology in Russia and abroad and launch El Lissitzky’s status as one of the leading figures in the avant garde.

“The artist constructs a new symbol with his brush. This symbol is not a recognizable form of anything that is already finished, already made, or already existent in the world – it is a symbol of a new world, which is being built upon and which exists by the way of the people.”

The exact meaning of “Proun” was never fully revealed, with some suggesting that it is a contraction of proekt unovisa (designed by UNOVIS) or proekt utverzhdenya novogo (Design for the confirmation of the new). Proun was essentially El Lissitzky’s exploration of the visual language of suprematism with spatial elements, utilizing shifting axes and multiple perspectives. Suprematism at the time was conducted almost exclusively in flat, 2D forms and shapes. El Lissitzky, with a taste for architecture and other 3D concepts, tried to expand suprematism beyond this. In Prouns, the basic elements of architecture – volume, mass, color, space and rhythm – were subjected to a fresh formulation in relation to the new suprematist ideals. Jewish themes and symbols also sometimes made appearances in his Prounen, usually with El Lissitzky using Hebrew letters as part of the typography or visual code. His Proun works (known as Prounen) spanned over a half a decade, evolving from straightforward paintings and lithographs into fully three-dimensional installations that laid the foundation for his later experiments in architecture (architectons) and exhibition design. Through his Prouns, utopian models for a new and better world were developed.

Bauhaus and De Stijl

In 1921, roughly concurrent with the demise of UNOVIS, suprematism was beginning to fracture into two ideologically adverse halves, one favoring Utopian, spiritual art and the other a more utilitarian art that served society. El Lissitzky was fully aligned with neither and left Vitebsk in 1921. He took a job as a cultural representative of Russia and moved to Berlin where he worked with and influenced important figures of the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements, most notably Kurt Schwitters, László Moholy-Nagy, and Theo van Doesburg. Together with Schwitters and van Doesburg, El Lissitzky presented the idea of an international artistic movement under the guidelines of constructivism while also working with Kurt Schwitters on the issue Nasci (Nature) of the periodical Merz, and continuing to illustrate children’s books.

Horizontal skyscrapers and exhibitions of the 1920s

In 1923–1925, El Lissitzky proposed and developed the idea of horizontal skyscrapers (Wolkenbügel, “cloud-irons”). Lissitzky argued that as long as humans cannot fly, moving horizontally is natural and moving vertically is not. Thus, where there is not sufficient land for construction, a new plane created in the air at medium altitude should be preferred to an American-style tower. These buildings, according to Lissitzky, also provided superior insulation and ventilation for their inhabitants.

“1926. My most important work as an artist begins: the creation of exhibitions.”

In June 1926, Lissitzky designed an exhibition room for the Internationale Kunstausstellung art show in Dresden and the Raum Konstruktive Kunst (Room for constructivist art) and Abstraktes Kabinett shows in Hanover, and perfected the 1925 Wolkenbügel concept in collaboration with Mart Stam.

One of his most notable exhibits was the All-Union Polygraphic Exhibit in Moscow in August–October 1927, where Lissitzky headed the design team for “photography and photomechanics” (i.e. photomontage) artists and the installation crew. His work was perceived as radically new, especially when juxtaposed with the classicist designs of Vladimir Favorsky (head of the book art section of the same exhibition) and of the foreign exhibits.

In the 1928 Press Show scheduled for April–May 1928 the Soviets rented the existing central pavilion, the largest building on the fairground and the Soviet program designed by Lissitsky revolved around the theme of a film show, with nearly continuous presentation of the new feature films, propagandist newsreels and early animation, on multiple screens inside the pavilion and on the open-air screens. His work was praised for near absence of paper exhibits; “everything moves, rotates, everything is energized” Lissitzky also designed and managed on site less demanding exhibitions like the 1930 Hygiene show in Dresden.

Final years

In 1932, Stalin closed down independent artists’ unions; former avant-garde artists had to adapt to the new climate or risk being officially criticised or even blacklisted. El Lissitzky retained his reputation as the master of exhibition art and management into late thirties. In 1941, his tuberculosis worsened, but he continued to produce works, one of his last being a propaganda poster for Russia’s efforts in World War II, titled “Davaite pobolshe tankov!” (Give us more tanks!) He died on December 30, 1941, in Moscow.